Spiritual Freedom Is Just as Important as Physical Freedom

by Josh Gerstein

by Josh Gerstein

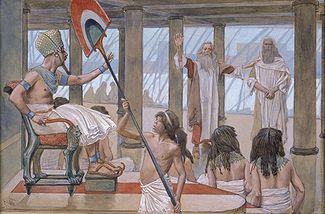

Parshat Shemot (Exodus) begins with the rise of a new Pharaoh in Egypt, and the subsequent enslavement and subjugation of the Jewish people under his regime. The text relates that Pharaoh appointed tax collectors over the Jewish people, and afflicted them with all kinds of hard manual labor.

The next chapters tell the story of the enslavement of the Jewish people in Egypt, culminating with the verses telling of the beginning of the redemption process:

After many days had passed the King of Egypt died, the children of Israel cried out from the hard work, and their cries went up before God, because of the work. God heard their cry, and He remembered His covenant with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. And God saw the children of Israel and God knew (Exodus 2:23–25).

The story of Exodus is among the most critical, central events in Jewish history, and it is one that has much to teach us for our times. Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik points out that the last verse of the above passage is seemingly redundant. It acknowledges that God both “heard” and “knew” the cries of the Jewish people, but doesn’t someone know of a matter the moment that he hears of it? If the Torah takes the opportunity to use both terms, it must be that there is a unique distinction between the meaning of “hearing” and “knowing” when it comes to the Divine.

Rav Soloveitchik’s insightful answer to this question not only solves the difficulty in the Biblical text, but also provides a deeper understanding of the concept of prayer and true freedom. He explains that if we take a closer look at the verse, “and their cries went up before God, because of the work,” we will notice that there is a specific reference to the source of the cries, i.e., the harsh labor. Why is this important?

Rav Soloveitchik explains that this qualification teaches an important lesson about slavery and freedom: “Slavery is not a monolithic concept; slavery has many expressions. There are many forms of enslaving, of taking a free human being and converting him into a bound man” (The Rav Thinking Aloud on the Parshah, Shemot).

The Jewish people suffered in Egypt from two forms of slavery. The first was a physical form of slavery that caused great pain and anguish, and so they cried out to God for relief. However, there was a second dimension to the enslavement — a spiritual enslavement, which was only subconsciously felt. It is important to note that this form of enslavement was not the reason for the cries of the people. The verse here is clear: The cries of the Jewish people were only a result of the harsh labor, the physical enslavement of which they had an acute awareness.

It is with this concept that Rav Soloveitchik answers our original question and discusses the matter of God both “hearing” and “knowing.” He explains that the seemingly redundant verse is not redundant at all; rather, its distinction is incredibly important and its message should serve as a source of comfort to every Jew who has ever turned to cry out to God in his hour of need.

Writes the Rav: “We would have been the most unfortunate people if HaKadosh Baruch Hu (God) had been guided by our prayer. Sometimes we pray for things that are a menace to us and sometimes we don’t pray for the things that are of the utmost importance to us.” During the story of Exodus, God heard the cries of the Jewish people and understood, i.e., He knew that which even they themselves did not know. Yes, the Jewish people needed relief from the physical enslavement, but it was the spiritual enslavement of which the people themselves were not aware that was truly hanging in the balance.

One of the most dramatic examples of the consequence of physical versus spiritual subjugation can be found in the life of Moses, the greatest leader of the Jewish people. The verses in Devarim (Deuteronomy) tell of the death of Moses and his burial outside of the Land of Israel in the land of Moab (Devarim 34:5–6.). The Midrash shares a fascinating insight into the reason why Moses was unable to be buried in the Land of Israel, which so fittingly relates to our discussion of the concept of spiritual subjugation. The Midrash writes:

Moses said to God, “Master of the Universe, Joseph’s bones entered the land, but I do not enter the Land?” The Holy One, Blessed be He, replied, “He who acknowledged his land is buried in his land; he who did not acknowledge his land is not buried in his land.” How do we know that Joseph acknowledged his land? His master’s wife said, “Look, he brought us a Hebrew man…” (Genesis 39:14) And Joseph did not deny it, rather, he said, “I was stolen away from the Land of the Hebrews” (ibid. 40:15.) You Moses, who did not acknowledge your Land, will not be buried in your land. How so? Yitro’s daughters said, “An Egyptian man saved us from the shepherds,” (Exodus 2:19.) and Moses heard this and remained silent. Therefore, he was not buried in his land (Devarim Rabbah 2:8).

Joseph identified as a Hebrew and was spiritually free, even though he lived a life of physical enslavement in the house of Potiphar. Moses, who was raised a free man in the house of Pharaoh, nevertheless experienced spiritual subjugation to the point where he did not identify himself as a Jew when presented to a stranger. It was this failing that destined Moses to his final resting place far from the home of the Jewish people. Physical freedom is a well-known value the world over, but we cannot underestimate the power and significance of spiritual freedom.

Police Stop Anti-Zionist Agitators From Accessing Florida University President’s Home as Students Revolt Nationwide

Police Stop Anti-Zionist Agitators From Accessing Florida University President’s Home as Students Revolt Nationwide Nearly One in Five Young People Sympathize With Hamas, 29% Say US Should Reduce or End Alliance With Israel: Poll

Nearly One in Five Young People Sympathize With Hamas, 29% Say US Should Reduce or End Alliance With Israel: Poll Ilhan Omar Silent After Daughter’s Arrest, Suspension for Role in Columbia University Anti-Israel Protest

Ilhan Omar Silent After Daughter’s Arrest, Suspension for Role in Columbia University Anti-Israel Protest Cultural Center Backed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Plans to Produce Films About Attack on Israel

Cultural Center Backed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Plans to Produce Films About Attack on Israel How Does Ilhan Omar Really Feel About Iran?

How Does Ilhan Omar Really Feel About Iran? This Passover, Combine Respect for Tradition with the Courage to Innovate

This Passover, Combine Respect for Tradition with the Courage to Innovate Israel’s Iran Attack Carefully Calibrated After Internal Splits, US Pressure

Israel’s Iran Attack Carefully Calibrated After Internal Splits, US Pressure Palestinian Cameramen Exposed in New Footage Documenting Oct. 7 Atrocities Side by Side with Terrorists

Palestinian Cameramen Exposed in New Footage Documenting Oct. 7 Atrocities Side by Side with Terrorists US Money to Convicted Terrorists; US Training to Aspiring Terrorists

US Money to Convicted Terrorists; US Training to Aspiring Terrorists Man Arrested in Paris After Iran Consulate Incident

Man Arrested in Paris After Iran Consulate Incident

Cultural Center Backed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Plans to Produce Films About Attack on Israel

Cultural Center Backed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Plans to Produce Films About Attack on Israel Ilhan Omar Silent After Daughter’s Arrest, Suspension for Role in Columbia University Anti-Israel Protest

Ilhan Omar Silent After Daughter’s Arrest, Suspension for Role in Columbia University Anti-Israel Protest Tehran Signals No Retaliation Against Israel After Drones Attack Iran

Tehran Signals No Retaliation Against Israel After Drones Attack Iran Nearly One in Five Young People Sympathize With Hamas, 29% Say US Should Reduce or End Alliance With Israel: Poll

Nearly One in Five Young People Sympathize With Hamas, 29% Say US Should Reduce or End Alliance With Israel: Poll Israeli Government Approves Increased Payments to Returned Gaza Hostages

Israeli Government Approves Increased Payments to Returned Gaza Hostages