25 Years Later: Silence and the Rabin Assassination

by Benjamin Kerstein

by Benjamin Kerstein

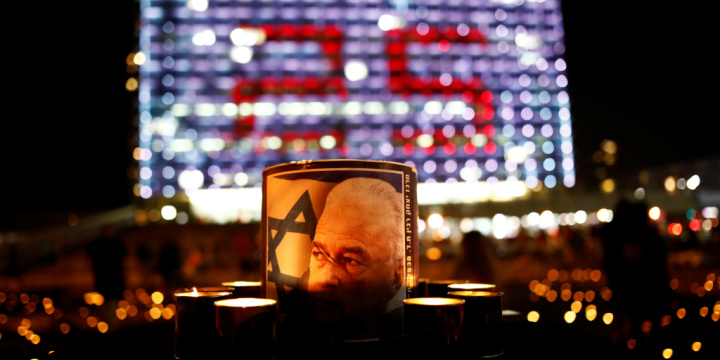

A candle holder with the photo of late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin printed on it is seen at Rabin Square, during a memorial event commemorating the 25th anniversary of Rabin’s assassination, in Tel Aviv, Israel, Photo: Oct. 29, 2020. Photo: Reuters / Corinna Kern.

On a late Saturday afternoon last week, I walked the 15 minutes from my Tel Aviv apartment to Rabin Square in order to view a place that seems now like a kind of event horizon of history: the cramped few square meters behind the City Hall where Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was murdered 25 years ago.

Even a quarter century later, the details remain terribly vivid: The euphoria of Rabin’s signing of the Oslo Accords with Yasser Arafat and the PLO, the terrifying atmosphere of incitement and violence that followed, and the enormous pro-peace demonstration at which Rabin spoke on the night of November 4, 1995.

After the demonstration, Rabin, flanked by several bodyguards, descended the back stairs of the City Hall to his waiting limousine. As he did so, a young man who had been loitering nearby for almost an hour circled the guards, drew a 9-mm Beretta pistol and fired three shots. Two of the bullets plowed into Rabin’s back, causing mortal damage to his lungs and spleen. Ten minutes later, after a mad dash to nearby Ichilov Hospital, doctors commenced heroic attempts at resuscitation, to no avail. It was later ascertained that Rabin had been clinically dead within minutes of the shooting.

There, where it happened, I felt the weight of tragedy. Flowers and yizkor candles were laid on the memorial to Rabin, along with wreaths and a few letters from children. Inlaid in the pavement are small brass fixtures, marking the spots where Rabin, his guards and the assassin stood at the moment the shots were fired. They make clear that in those fateful seconds, Rabin and his killer were no more than centimeters apart. The assassin quite literally walked right up to him.

Despite the pandemic, a few people were milling around, their heads bowed, taking in the scene. The silence felt enormous.

The assassin was a right-wing extremist named Yigal Amir. He remains imprisoned for life, but still haunts Israel much as Lee Harvey Oswald and John Wilkes Booth still haunt the United States. That he was not killed like Oswald and Booth, or executed for his crime, means he is always somehow there, a constant reminder that it happened here, and could happen again. And his shadow presence forces on us the question of the legacy of his act. Put simply, did Yigal Amir “win”?

Given that Amir’s stated goal was to stop the peace process with the Palestinians and prevent Israel from handing over the West Bank and Gaza Strip, one can make a plausible argument that he won at least a partial victory. Rabin’s death did not end the peace process, but it badly damaged it, and many of Rabin’s admirers see its eventual failure as an inevitable result of the assassination, particularly after the eruption of the Second Intifada ultimately ushered in the long reign of the right — culminating in Benjamin Netanyahu’s decade in power.

This is especially galling to Rabin’s partisans, who view Netanyahu as responsible for the killing due to his failure to condemn the incendiary right-wing rhetoric against Rabin. Did the incitement truly cause the murder? The Right vehemently denies it, but I often feel it protests too much. Not everyone on the right engaged in such incitement, but a great many — especially in the settlement movement — were happy to call Rabin a Nazi, a collaborator, a traitor and a murderer. Was Netanyahu himself culpable in this? Not entirely. He made some statements against incitement, but there is no doubt he could have done more. However, 25 years have passed, and it seems time for the Right to make amends. There is no shame in admitting that, a long time ago, it acted disgracefully. The Right can acknowledge, I think, that it sinned while still holding that its sins fell short of murder.

For the Left, however, there is also a terrible question to be faced: namely, was the Right, in fact, correct? Not in its incitement, of course, but in its essential critique of Oslo — that it would be a disaster and badly damage Israel’s security. However much many of us may want to deny it, it seems it was right. It is undeniable that in 2000, Ehud Barak offered Arafat a great deal more than Rabin would have, and the result was the refusal of peace and terrorism on a massive scale. The idea that, by some magic of personality, Rabin could have been more successful seems implausible at best.

Twenty-five years later, then, Israel seems no closer to resolving the terrible conundrum of Rabin and his death. In the end, there is no one to conclusively blame but the small, petty fanatic sitting in prison who said emphatically, “I have no regrets.” But everyone knows there is more to it than that. That there are terrible unanswered questions on that event horizon of history, the black hole of murder from which no light can escape.

Perhaps the real lesson is one that not just Israelis but the entire Jewish people must learn, especially with the ferocious divisions that still rend our people: we are not so different from everyone else. We too can be hateful, violent, fanatical, insane. We too can be assassins. We too can be murderers. And above all, we must choose not to be. This is, perhaps, the only thing that Rabin’s terrible death has to teach us. The rest is silence.

Benjamin Kerstein is a columnist and Israel Correspondent for the Algemeiner. His website can be viewed here.

US Stops UN From Recognizing a Palestinian State Through Membership

US Stops UN From Recognizing a Palestinian State Through Membership Jordan Reaffirms Commitment to Peace With Israel After Iran Attack, Says Ending Treaty Would Hurt Palestinians

Jordan Reaffirms Commitment to Peace With Israel After Iran Attack, Says Ending Treaty Would Hurt Palestinians ‘Crisis at Columbia’: Elite University Spirals Into Chaos Against Backdrop of School President’s DC Testimony

‘Crisis at Columbia’: Elite University Spirals Into Chaos Against Backdrop of School President’s DC Testimony ‘A Time for Vigilance’: FBI Director Says Agency on Alert for Threats Against Jewish Community During Passover

‘A Time for Vigilance’: FBI Director Says Agency on Alert for Threats Against Jewish Community During Passover New Haggadah Released for Israeli Soldiers in Gaza Ahead of Passover

New Haggadah Released for Israeli Soldiers in Gaza Ahead of Passover ADL Data Reveals Alarming Campus Antisemitism, Despite Strong Jewish Life

ADL Data Reveals Alarming Campus Antisemitism, Despite Strong Jewish Life New Hospital Approved for Construction in Southern Israel Amid Gaza War

New Hospital Approved for Construction in Southern Israel Amid Gaza War UN Security Council to Vote Thursday on Palestinian UN Membership

UN Security Council to Vote Thursday on Palestinian UN Membership New Play Opening in NY Recounts Verbatim Testimonies From Oct. 7 Survivors, Families of Victims

New Play Opening in NY Recounts Verbatim Testimonies From Oct. 7 Survivors, Families of Victims

UN Security Council to Vote Thursday on Palestinian UN Membership

UN Security Council to Vote Thursday on Palestinian UN Membership New Hospital Approved for Construction in Southern Israel Amid Gaza War

New Hospital Approved for Construction in Southern Israel Amid Gaza War ADL Data Reveals Alarming Campus Antisemitism, Despite Strong Jewish Life

ADL Data Reveals Alarming Campus Antisemitism, Despite Strong Jewish Life Iran Could Review ‘Nuclear Doctrine’ Amid Possibility of Israeli Strike, Iranian Commander Warns

Iran Could Review ‘Nuclear Doctrine’ Amid Possibility of Israeli Strike, Iranian Commander Warns New Haggadah Released for Israeli Soldiers in Gaza Ahead of Passover

New Haggadah Released for Israeli Soldiers in Gaza Ahead of Passover