The Founding Fathers of Israel’s Scientific Legacy

by Jacob Sivak

by Jacob Sivak

While technically a failure, the crash landing of an Israeli space probe on the moon’s surface was successful in many respects. It was also the first privately-funded moon trip, and showcased the inventive and ambitious aspect of Israeli science.

And what are the foundations of these achievements?

One hundred years ago, Fritz Haber received the Nobel Prize for discovering how to produce ammonia from Nitrogen and Hydrogen gases — a discovery some consider the most important of the 20th century because of its importance to the production of fertilizer (50% of the food produced in the world today makes use of this process).

It was also important in the production of explosives. The German war effort during World War I was hampered by the lack of access to natural nitrates essential for producing ammunition. In Sapiens, Yuval Harari notes that without Haber’s discovery, Germany’s military effort during World War I would have faltered much earlier than it did. Haber is also considered to be the father of chemical warfare for his role in the development and use of poison gas as a weapon.

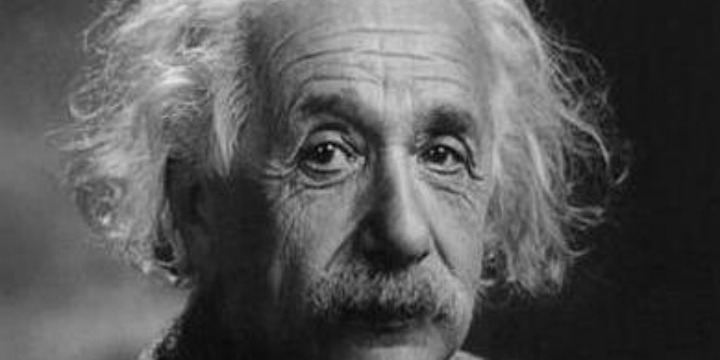

Haber had a long and intimate friendship with Albert Einstein. While both scientists came from somewhat non-observant German-Jewish backgrounds, Haber was a patriotic German who supported German militarism and believed in Jewish assimilation. Einstein was a pacifist opposed to nationalism.

Haber converted to Christianity to further his career, and was eventually named to the powerful position of Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Einstein, on the other hand, was keenly aware of the racial basis of German antisemitism. In a piece in The Times (London) in 1919 about whether his theory of relativity would be proven correct, Einstein wrote: “today I am described in Germany as a German savant, and in England as a ’Swiss Jew.’ Should it ever be my fate to be represented as a bête noire, I should, on the contrary, become a ‘Swiss Jew’ for the Germans and a ‘German savant’ for the English.”

While Einstein was never a “card-carrying” Zionist, he did support the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In Einstein: His Life and Universe, Walter Isaacson notes that Einstein wrote to Haber that, “I have always felt an obligation to stand up for my persecuted and morally oppressed tribal companions.” In 1921, Einstein and Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization, traveled to the United States to raise funds for the establishment of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Weizmann came from a traditional Jewish background in Eastern Europe. Like Haber, he was a brilliant chemist (he taught at the University of Manchester), who made an important contribution to the war effort for his adopted country, England. Acetone, an ingredient crucial in the production of Cordite, an explosive used by the British forces during World War I, was in short supply. Weizmann developed a bacterial fermentation process to produce large quantities of acetone, which was critical to the success of the British war effort. It brought him into contact with Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, and David Lloyd George, Minister of Munitions, and encouraged Arthur Balfour, the Foreign Secretary, to issue the Balfour Declaration, in which the British government agreed to support the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Despite his conversion, Haber was forced to leave Germany when the Nazis came to power. He left, but not before helping Jewish scientists at his institute find positions abroad. In 1933, Haber spent some time in England, where Weizmann offered him the directorship of a new research center, the Daniel Sieff Institute (now the Weizmann Institute) in Palestine. Haber died of a heart attack in Basel, Switzerland, in early 1934, while on his way to Palestine.

Weizmann continued to work on behalf of the Zionist movement, becoming the first president of Israel in 1949. When he died in 1952, the position was offered to Einstein. While deeply moved by the offer, he declined. Einstein died in 1955.

At the 1949 inauguration of the Weizmann Institute of Science, Weizmann prophetically stated: “We live, as you know, in a pioneering country. … Science is … our vessel of strength.”

Police Stop Anti-Zionist Agitators From Accessing Florida University President’s Home as Students Revolt Nationwide

Police Stop Anti-Zionist Agitators From Accessing Florida University President’s Home as Students Revolt Nationwide Nearly One in Five Young People Sympathize With Hamas, 29% Say US Should Reduce or End Alliance With Israel: Poll

Nearly One in Five Young People Sympathize With Hamas, 29% Say US Should Reduce or End Alliance With Israel: Poll Ilhan Omar Silent After Daughter’s Arrest, Suspension for Role in Columbia University Anti-Israel Protest

Ilhan Omar Silent After Daughter’s Arrest, Suspension for Role in Columbia University Anti-Israel Protest Cultural Center Backed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Plans to Produce Films About Attack on Israel

Cultural Center Backed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Plans to Produce Films About Attack on Israel How Does Ilhan Omar Really Feel About Iran?

How Does Ilhan Omar Really Feel About Iran? This Passover, Combine Respect for Tradition with the Courage to Innovate

This Passover, Combine Respect for Tradition with the Courage to Innovate Israel’s Iran Attack Carefully Calibrated After Internal Splits, US Pressure

Israel’s Iran Attack Carefully Calibrated After Internal Splits, US Pressure Palestinian Cameramen Exposed in New Footage Documenting Oct. 7 Atrocities Side by Side with Terrorists

Palestinian Cameramen Exposed in New Footage Documenting Oct. 7 Atrocities Side by Side with Terrorists US Money to Convicted Terrorists; US Training to Aspiring Terrorists

US Money to Convicted Terrorists; US Training to Aspiring Terrorists Man Arrested in Paris After Iran Consulate Incident

Man Arrested in Paris After Iran Consulate Incident

Nearly One in Five Young People Sympathize With Hamas, 29% Say US Should Reduce or End Alliance With Israel: Poll

Nearly One in Five Young People Sympathize With Hamas, 29% Say US Should Reduce or End Alliance With Israel: Poll Israeli Government Approves Increased Payments to Returned Gaza Hostages

Israeli Government Approves Increased Payments to Returned Gaza Hostages Police Stop Anti-Zionist Agitators From Accessing Florida University President’s Home as Students Revolt Nationwide

Police Stop Anti-Zionist Agitators From Accessing Florida University President’s Home as Students Revolt Nationwide Amazon Pulls Book by Hamas Leader Yahya Sinwar Referencing Oct. 7 Attacks After UK Lawyers Intervene

Amazon Pulls Book by Hamas Leader Yahya Sinwar Referencing Oct. 7 Attacks After UK Lawyers Intervene Man Arrested in Paris After Iran Consulate Incident

Man Arrested in Paris After Iran Consulate Incident