Ki Tavo: Jewish Identity and the Message of the First Fruits

by Josh Gerstein

by Josh Gerstein

Jews and Judaism represent a peculiar phenomenon that is found nowhere else in the world: Jews are a nation and Judaism is a religion, yet these two distinct identities are inseparably and uniquely intertwined.

Taking a look at the various countries around the world, we find nations that contain many different religions, as well as religions whose adherents are spread across many different nations. But what is unique about Jews and Judaism is that it combines nationalism and religion together.

On the one hand, Judaism contains all of the trappings of religious ritual and ceremony; on the other hand, it contains a national homeland — Israel — along with a rich and diverse national history and heritage.

In his work Kol Dodi Dofek, Rabbi J.B. Soloveitchik elucidates this fascinating duality by using the two covenants made with the Jewish people as his guiding light. He explains that there were two covenants made between God and the Jewish People: the Covenant of Fate and the Covenant of Destiny.

According to Rav Soloveitchik, the Covenant of Fate was born in the land of Egypt in the story of the Exodus, when God said, “And I shall take you unto me for a people, and I will be to you a God.” (Exodus 6:7)

This covenant expresses the camaraderie and interconnectivity of the Jewish nation in a historical and national context. Firstly, the Covenant of Fate signifies that an individual Jew will not, for better or for worse, be able to escape the fate of his people. We have seen this countless times, including with the destruction of European Jewry — where the annihilators made no distinction between rich or poor, educated or simple, or religious or secular. All Jews shared a part in the Covenant of Fate.

Yet positively speaking, this concept of a collective fate also leads to shared empathy; thus, when one Jew suffers, “I am with him in his distress.” (Psalms 91: 15) The knowledge of this shared fate arouses feelings of shared responsibility and shared action for the benefit of each other and the nation as a whole.

On the other hand, the Covenant of Destiny does not bind the Jewish people to one another in a national or historical way, but rather attaches them to their Creator through the religious and spiritual practices of Judaism. This was brought forth at the revelation at Sinai, where it is written, “And he [Moses] took the book of the covenant…” (Exodus 24:7).

This Covenant of Destiny is no less important than the Covenant of Fate in ensuring the continuation of Jewish national life.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, the former chief rabbi of the British Commonwealth, explains that during the 2,000 years of Jewish exile from their homeland, they continued to see themselves as one united nation. In his book Future Tense, Rabbi Sacks writes: “Wherever Jews were, they kept the same commandments, studied the same sacred texts. … These invisible strands of connection sustained them in a bond of collective belonging that had no parallel among any other national grouping.”

Throughout Jewish history, there has been an up-and-down relationship, whereby at certain stages the Covenant of Fate would take the forefront to unite us, and at other times, the Covenant of Destiny would be the more dominant force. But, as Rabbi Sacks writes, “It is that double bond that has held the Jews together. When one failed the other came to the fore.”

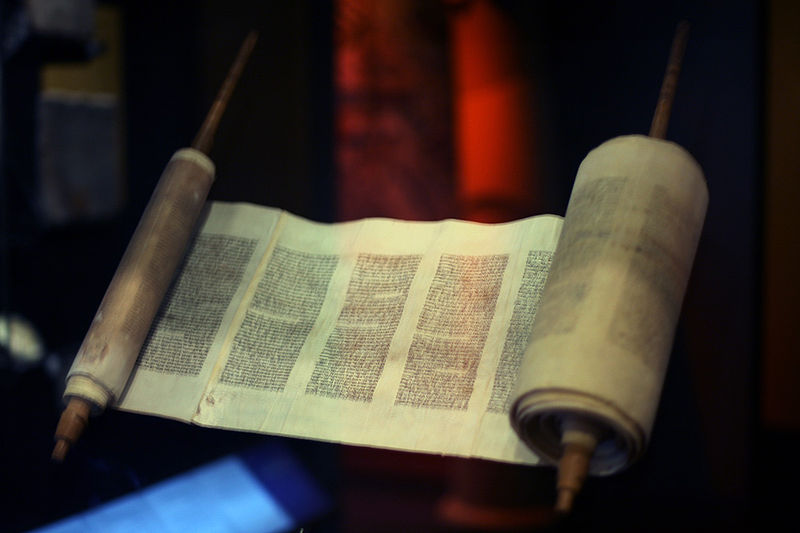

The concept of the Covenant of Fate and the Covenant of Destiny also seems to emerge in the beginning of Parshat Ki Tavo, which opens with the command to the Jewish people to bring the first fruits of the harvest to the Temple in Jerusalem. In addition to bringing the fruits to the Temple, the owner of the produce would also recite a declaration when he handed over his fruits to the Kohen (Priest). He would say, “I declare today to Hashem your God, that I have come to the land that Hashem swore to our forefathers to give us. … An Aramean tried to destroy my father. He descended to Egypt … there he became a nation-great. … The Egyptians mistreated and afflicted us. … Then we cried out to Hashem. … He took us out of Egypt. … He brought us to this place and he gave us this land.”

At first glance, this whole declaration is a bit of an oddity, and altogether unfitting for the ritual at hand. On such an occasion, we would assume to find words of thanksgiving to God for the produce — yet the declaration instead recounts the history of the Jewish people from their inception until they entered the Land of Israel.

What is the connection between the bringing of the first fruits and this historical overview of the Jewish people?

Martin Buber, in his article “Bikkurim”(First Fruits), offers a fascinating explanation:

Gifts offered to the gods from the first of the harvest are a familiar phenomenon of all cultures … as are prayers … thanking the gods for the blessing of the land. .. But of all these types of prayers in the world, I know of only one in which the worshipper praises God for having given him a LAND. … Even in later generations, the bearer of the bikkurim is not to say, for example, “My forefathers came to the land,” but rather, ” have come to the land.” Here the two entities addressed by the Torah, the nation and the individual, come together. “I have come to the land” means, first and foremost, “I — the nation of Israel — have come to the land.” The speaker identifies with Am Yisrael and speaks in the name of the nation. The significance of this is as follows: I testify and identify myself as a person who has come to the land. … Every farmer in every generation of Israel thanks God when he brings his bikkurim for the land to which He brought HIM. (Translation by Rabbi Elchanan Samet)

The purpose of the Bikkurim is that every year, the owner would have the opportunity to reaffirm his thanks and appreciation for having been brought to the Land of Israel and for living in connection to the very People of Israel — the Covenant of Fate. At the same time, the entire ceremony and declaration is recited in the sanctuary of the Temple — the physical home and working manifestation of the Covenant of Destiny.

In our times, with the loss of the Temple and the cessation of the Bikkurim, how can one practically keep the connection to the Covenant of Fate and the Covenant of Destiny alive? Rav Soloveitchik writes:

The Jew who believes in Knesset Israel (the Jewish People) is the Jew who lives as part of it wherever it is and is willing to give his life for it, feels its pain, rejoices with it, fights in its wars, groans at its defeats and celebrates its victories. The Jew who believes in Knesset Israel is a Jew who binds himself with inseverable bonds not only to the People of Israel of his own generation, but to the community of Israel throughout the ages. How so? Through the Torah, which embodies the spirit and the destiny of Israel from generation to generation unto eternity.

Through taking an active role and participating in the continued journey of the fate and destiny of the Jewish people, through harnessing the power and strength of our shared tradition, and through steadfastly nurturing a connection to our national homeland, unshakable bonds will unite all Jews under one banner — wherever they may be.

The author is a Jerusalem-based rabbi and Jewish educator. He served as a non-commissioned officer in the IDF Rabbinate, and is the author of the book “A People, A Country, A Heritage-Torah Inspiration from the Land of Israel.” http://www.apeoplecountryheritage.com/

Cultural Center Backed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Plans to Produce Films About Attack on Israel

Cultural Center Backed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Plans to Produce Films About Attack on Israel How Does Ilhan Omar Really Feel About Iran?

How Does Ilhan Omar Really Feel About Iran? This Passover, Combine Respect for Tradition with the Courage to Innovate

This Passover, Combine Respect for Tradition with the Courage to Innovate Israel’s Iran Attack Carefully Calibrated After Internal Splits, US Pressure

Israel’s Iran Attack Carefully Calibrated After Internal Splits, US Pressure Palestinian Cameramen Exposed in New Footage Documenting Oct. 7 Atrocities Side by Side with Terrorists

Palestinian Cameramen Exposed in New Footage Documenting Oct. 7 Atrocities Side by Side with Terrorists US Money to Convicted Terrorists; US Training to Aspiring Terrorists

US Money to Convicted Terrorists; US Training to Aspiring Terrorists Man Arrested in Paris After Iran Consulate Incident

Man Arrested in Paris After Iran Consulate Incident Amazon Pulls Book by Hamas Leader Yahya Sinwar Referencing Oct. 7 Attacks After UK Lawyers Intervene

Amazon Pulls Book by Hamas Leader Yahya Sinwar Referencing Oct. 7 Attacks After UK Lawyers Intervene Israeli Government Approves Increased Payments to Returned Gaza Hostages

Israeli Government Approves Increased Payments to Returned Gaza Hostages Tehran Signals No Retaliation Against Israel After Drones Attack Iran

Tehran Signals No Retaliation Against Israel After Drones Attack Iran

Man Arrested in Paris After Iran Consulate Incident

Man Arrested in Paris After Iran Consulate Incident US Money to Convicted Terrorists; US Training to Aspiring Terrorists

US Money to Convicted Terrorists; US Training to Aspiring Terrorists Palestinian Cameramen Exposed in New Footage Documenting Oct. 7 Atrocities Side by Side with Terrorists

Palestinian Cameramen Exposed in New Footage Documenting Oct. 7 Atrocities Side by Side with Terrorists US to Oppose Palestinian Bid for Full UN Membership

US to Oppose Palestinian Bid for Full UN Membership Israel’s Iran Attack Carefully Calibrated After Internal Splits, US Pressure

Israel’s Iran Attack Carefully Calibrated After Internal Splits, US Pressure