Remembering Yitzhak Shamir

by Moshe Phillips

by Moshe Phillips

The public longs for the good old days, when our leaders saw politics as a calling or a mission, not merely another job — one that’s a way station to becoming rich.” — Moshe Arens in The Jerusalem Post, June 4, 2008.

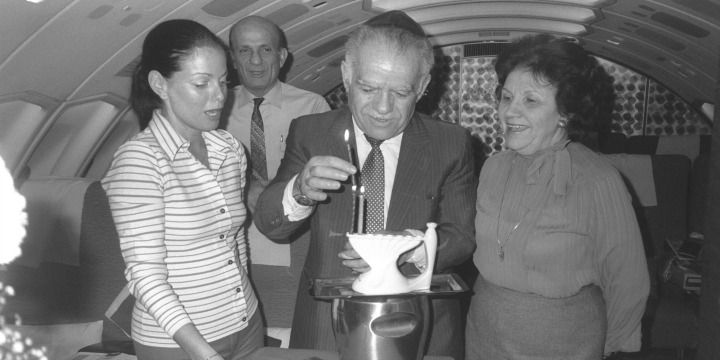

June 30th marks the seventh anniversary of the passing of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir. At Shamir’s Jerusalem funeral in 2012, Shimon Peres, his longtime political adversary, had this to say: “Yitzhak Shamir was a fighter. For his people. For his country. For his way. Many times, we were at odds with one another. Our positions on the regional situation were different. But the two of us were convinced that we both were working as Israelis devoted to their country and who love their land.”

That Shamir’s resting place would be in Jerusalem is certainly most fitting. The slogan of the LEHI underground that he led in the 1940s was a quote from Psalm 136: “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem.”

Shamir’s involvement in leadership roles in the Zionist movement spanned nearly his entire adult life: underground fighter, intelligence officer, Soviet Jewry activist, politician, statesman, and prime minister. Shamir was all of these and much more.

Shamir dedicated his life to the realization of the Zionist dreams of Theodor Herzl and Ze’ev Jabotinsky.

But did the public ever really get to know the real Yitzhak Shamir? He did not seek publicity, and did not like to talk about himself.

Shamir was born in 1915 in Belarus. When he was still a student, he threw himself heavily into the militant activities of the Betar Zionist youth movement. It was there that he was first exposed to the philosophy that would form the ideals that served him as his focus for the rest of his life.

Ze’ev Jabotinsky taught the young members of Betar both military strategy and military discipline. Jabotinsky demanded a spirit of dedication to the development of a Jewish homeland in the land of Israel, and his young followers were educated to believe that sacrifice for the establishment of a Jewish state was an honor and a duty.

Shamir decided to immigrate to the British-controlled Palestine Mandate in 1935. In Tel Aviv, Shamir joined other Zionist activists he knew from Poland, and became an Irgun underground fighter.

When Avraham “Yair” Stern led a group of his followers out of the Irgun and formed the Fighters for the Freedom of Israel, also known by its acronym LEHI, Shamir left with him. Menachem Begin had not yet arrived in the Mandate to lead the Irgun’s revolt against the British.

The goal of LEHI was to force the British to quit the Mandate, and thus allow a Jewish state to be formed. Shamir was arrested and imprisoned by the British for his underground activities. Shamir escaped from the British, and in doing so helped to make the “Stern Gang” even more legendary.

After the February 1942 assassination of Stern by British CID (Central Investigation Department) officers, Shamir became one of the three-man Central Committee that would lead LEHI for the next six years.

In November 1944, two LEHI soldiers assassinated Lord Moyne, the British Resident Minister in the Middle East. Shamir was believed to have trained the two gunmen, and planned the assassination. Shamir was captured by the British again in 1946, and in 1947 he escaped — this time from a British detention camp in Eritrea in Africa.

Shamir would not return to Israel until 1948, just days after the establishment of the Jewish state that he had struggled for so many years to create.

When the British submitted the issue of the Mandate to the United Nations and the UN approved a partition plan that called for the establishment of a Jewish state and an Arab state, LEHI had accomplished part of its goal. Most of LEHI’s other objectives — the establishment of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, Jewish sovereignty over all of the historic land of Israel, and the bringing of the Jewish masses from the Diaspora to Israel were still left unfulfilled.

After UN mediator Count Bernadotte’s assassination, LEHI leaders were rounded up and arrested by David Ben-Gurion’s provisional government.

LEHI’s commanders formed a political party, the Fighter’s Party, in order to bring about the release of Nathan Yellin-Mor, another LEHI leader. The Fighter’s Party received less than one percent of the vote in its first election, and officially disbanded shortly before the next elections were held. LEHI leaders chose different paths, and never worked together again.

After the establishment of the State of Israel, Shamir struggled for success in various business ventures. In 1955, he joined the Mossad, Israel’s intelligence service, and held a senior position in Europe.

After his retirement from the Mossad in the mid-1960s, Shamir returned to Israel and became active in the Soviet Jewry freedom movement. In 1970, he joined Menachem Begin’s Herut Party.

Shamir became a member of the Knesset in 1974. In 1975, he was elected chairman of the Herut Executive Committee, and in 1977 he was elected speaker of the Knesset.

In 1980, Begin named Shamir foreign minister. In that position, he helped implement the retreat from Sinai that Begin had negotiated with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat at Camp David, even though he had not voted in favor of the accords.

When Begin resigned from office in October of 1983, Shamir became prime minister. Americans had no idea who he was. In the 1984 election, Shamir was unable to maintain power and entered into a National Unity government with Shimon Peres, where a rotation of posts occurred. Shamir served as deputy prime minister and foreign minister from 1984-1986, and prime minister from 1986-1988.

Shamir formed a coalition government in 1988 with various mid-size religious parties and smaller right-leaning parties, and became prime minister. In 1992, Israel again held Knesset elections, and this time Yitzhak Rabin and the Labor Party won more seats — Rabin formed the next government.

Shamir, defeated, all but retired from public life. He rarely made public appearances or public statements. He did, however, publicly express his strong opposition to Rabin’s decision to sign agreements with Yasser Arafat and the PLO.

Shamir’s autobiography, Summing Up, was published in 1994. His public involvement in current events continued to be rare, although he did enter the debate over the status of Hebron.

In one of his last public acts, he joined with an eclectic group of politicians from across the Israeli political spectrum and voiced his opposition to the direct election of Israel’s prime minister. The direct election scheme was eventually abandoned.

For decades, many in Israel and in the US tried to minimize the impact that Shamir’s LEHI had on London’s decision to end the British Mandate. LEHI’s history began to be taught in earnest when Shamir became Israel’s leader. With Shamir’s death, many had hoped that perhaps LEHI would finally have its story fully told and receive the fair treatment it was denied for far too long. There is still much work that is needed to be done on this front.

Moshe Phillips is national director of Herut North America’s US division. Herut is an international movement for Zionist pride and education and is dedicated to the ideals of pre-World War II Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky. Herut’s website is https://herutna.org/.

Network Behind Eruption of Anti-Israel College Campus Protests Revealed in New Report

Network Behind Eruption of Anti-Israel College Campus Protests Revealed in New Report US Issues Further Sanctions on Iran, Targets Drones

US Issues Further Sanctions on Iran, Targets Drones UN Rapporteur With History of Anti-Israel Animus Supports Pro-Hamas Protests on College Campuses

UN Rapporteur With History of Anti-Israel Animus Supports Pro-Hamas Protests on College Campuses We Need to Invest in Academic Research on Antisemitism Now

We Need to Invest in Academic Research on Antisemitism Now US Academic Skews Stats to Compare Gaza to Actual Case of Genocide

US Academic Skews Stats to Compare Gaza to Actual Case of Genocide WIll Israel-Iran Conflict Spiral Out of Control — or Will Both Sides Play It Safe?

WIll Israel-Iran Conflict Spiral Out of Control — or Will Both Sides Play It Safe? It’s All About ‘Time’: Israel Cannot Survive If It Does Not Address Iranian Nuclear Weapons

It’s All About ‘Time’: Israel Cannot Survive If It Does Not Address Iranian Nuclear Weapons US, 17 Other Countries Urge Hamas to Release Hostages, End Gaza Crisis

US, 17 Other Countries Urge Hamas to Release Hostages, End Gaza Crisis Iranian, 2 Others Detained in Peru Over Plot to Kill Israelis

Iranian, 2 Others Detained in Peru Over Plot to Kill Israelis Iran Sentences Rapper Toomaj Salehi to Death Over 2022-23 Unrest

Iran Sentences Rapper Toomaj Salehi to Death Over 2022-23 Unrest

US Academic Skews Stats to Compare Gaza to Actual Case of Genocide

US Academic Skews Stats to Compare Gaza to Actual Case of Genocide We Need to Invest in Academic Research on Antisemitism Now

We Need to Invest in Academic Research on Antisemitism Now UN Rapporteur With History of Anti-Israel Animus Supports Pro-Hamas Protests on College Campuses

UN Rapporteur With History of Anti-Israel Animus Supports Pro-Hamas Protests on College Campuses US Issues Further Sanctions on Iran, Targets Drones

US Issues Further Sanctions on Iran, Targets Drones Network Behind Eruption of Anti-Israel College Campus Protests Revealed in New Report

Network Behind Eruption of Anti-Israel College Campus Protests Revealed in New Report