Dreyfus’ Long Shadow for American Jews

by Harold Brackman

by Harold Brackman

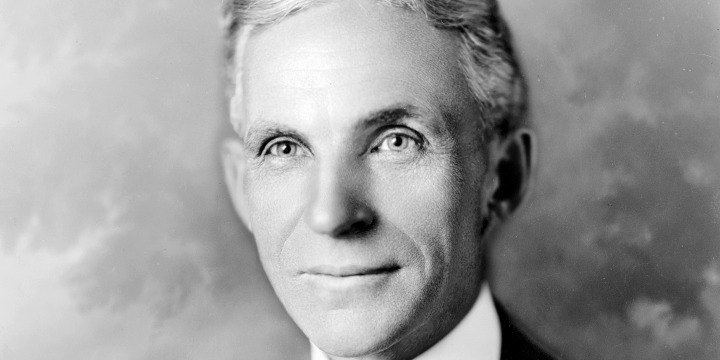

The post-World War I period — including 1919’s Red Scare, passage of racist immigration restriction acts, mass KKK marches on the nation’s capital, and Henry Ford’s publication of his four-volume The International Jew (1921) — was traumatic for American Jews.

Twenty years earlier, French Captain Alfred Dreyfus’ long ordeal (1894-1906) on trumped-up treason charges had been what Hannah Arendt called “a huge dress rehearsal” for 20th century antisemitism.

Despite scattered calls by Jews for a boycott of 1900’s Paris Exposition, cautious American rabbis usually preferred to criticize Dreyfus’ imprisonment on Devil’s Island as a miscarriage of justice, not an anti-Jewish crime. Even so, the Dreyfus Affair was a wake-up call about antisemitism for Americans like Mark Twain who lauded Dreyfus’ chief defender, Émile Zola.

During the 1920s, America became transfixed by the Sacco-Vanzetti Case, involving two Italian American anarchists convicted of armed robbery and murder, but the Dreyfus Affair still reverberated. In 1919, there had been the now mostly-forgotten “American Dreyfus Case.” Henry Ford used his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, to pressure the US Justice Department into torturing confessions out a wartime Jewish army officer named Rosenbluth, ultimately exonerated after being falsely accused of murdering another soldier during target practice.

American literature also manifested Jazz Age antisemitism. The most famous antisemitic caricature was Robert Cohn in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1925). Cohn is introduced as “the middleweight boxing champion of Princeton,” a “kike,” and a “rich Jew”; he is obnoxious and abuses women. Hemingway’s model for Cohn was Harold Loeb, his former friend and literary benefactor.

Second to Cohn in the rogues’ gallery of Jewish villains was Meyer Wolfsheim, underworld mentor of the hero in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925). Wolfsheim, described as having a hideous nose, was modeled on Arnold Rothstein, the Jewish gambler reputed to have fixed the 1919 World Series. Some critics argue that Fitzgerald also meant to hint that his anti-heroic hero, Jay Gatsby (or Gatz), a mystery man claiming vague origins, was himself a Jew passing as a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant.

The 1920s’ two most celebrated women novelists also created problematic Jewish characters. Edith Wharton’s A Son At the Front (1923) features Jorgenstein, a fat, red, international banker, with an “air of bloated satisfaction” and talent for unpatriotic “vile money-making.” Another Jewish character, Léonce Black, has “plump eyelids” and strokes “his Assyrian nose as though its handsome curve followed the pure Delphic line.” He hides out in Paris rather than fight the Germans.

Willa Cather’s The Professor’s House (1925) introduces Louie Marsellus, amidst classic antisemitic stereotypes of hording gold and jewels. He made his money during World War I, but did not serve. The hero, Tom Outland, before his death fighting the Germans, has this exchange with Roddy Blake, whom he accuses of robbing America’s Indian burial grounds for profit: “You’ve gone and sold your country’s secrets, like Dreyfus.”

Another character’s response indicates that Cather actually knew Dreyfus was innocent. Yet she put this slander in the mouth of her hero, implying that a Jew always betrays his country.

Such was the power of post-war literary antisemitism.

Historian Harold Brackman is coauthor with Ephraim Isaac of From Abraham to Obama: A History of Jews, Africans, and African Americans (Africa World Press, 2015).

Palestinian Prime Minister Announces New Reform Package

Palestinian Prime Minister Announces New Reform Package France: Man Suspected of Abducting, Raping Jewish Woman ‘to Avenge Palestine’

France: Man Suspected of Abducting, Raping Jewish Woman ‘to Avenge Palestine’ Israel Intensifies Strikes Across Gaza, Orders New Evacuations in North

Israel Intensifies Strikes Across Gaza, Orders New Evacuations in North Iran Threatens to Annihilate Israel Should It Launch a Major Attack

Iran Threatens to Annihilate Israel Should It Launch a Major Attack ‘Completely Baseless’: Reports of Mass Graves at Gaza Hospitals are False, IDF Says

‘Completely Baseless’: Reports of Mass Graves at Gaza Hospitals are False, IDF Says Columbia University Shutters Campus as Jews Fear for Safety, Critics Call for President to Resign

Columbia University Shutters Campus as Jews Fear for Safety, Critics Call for President to Resign ‘Hamas, We Love You!’ A List of the Chants, Statements From Columbia University’s ‘Gaza Solidarity Encampment’

‘Hamas, We Love You!’ A List of the Chants, Statements From Columbia University’s ‘Gaza Solidarity Encampment’ ‘Useless Pigs’: Anti-Israel Demonstrations Rage at Yale University, Forcing Police Intervention

‘Useless Pigs’: Anti-Israel Demonstrations Rage at Yale University, Forcing Police Intervention Anti-Israel Protesters Interrupt Chelsea Handler Comedy Show Because of Her Support for Jewish State

Anti-Israel Protesters Interrupt Chelsea Handler Comedy Show Because of Her Support for Jewish State Israeli Hostage Families Make Passover Plea for Return of Missing Loved Ones

Israeli Hostage Families Make Passover Plea for Return of Missing Loved Ones

‘Completely Baseless’: Reports of Mass Graves at Gaza Hospitals are False, IDF Says

‘Completely Baseless’: Reports of Mass Graves at Gaza Hospitals are False, IDF Says Iran Threatens to Annihilate Israel Should It Launch a Major Attack

Iran Threatens to Annihilate Israel Should It Launch a Major Attack Israel Intensifies Strikes Across Gaza, Orders New Evacuations in North

Israel Intensifies Strikes Across Gaza, Orders New Evacuations in North France: Man Suspected of Abducting, Raping Jewish Woman ‘to Avenge Palestine’

France: Man Suspected of Abducting, Raping Jewish Woman ‘to Avenge Palestine’ Palestinian Prime Minister Announces New Reform Package

Palestinian Prime Minister Announces New Reform Package