New Film Chronicles the Surprising Story of Jewish Renewal in Africa

by Bernard Starr

by Bernard Starr

Suppose you’re a young Jewish woman on a six-month volunteer mission with a women’s rights group in Ghana. Your passion for women’s issues helps you dismiss your initial wariness in this strange setting. Then the Jewish New Year celebrations — Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur — approach, and you long for the holiday celebrations back home.

So what does a wandering Jew do? She looks for a synagogue. But a synagogue in Ghana?

So she asks about one.

Most people are puzzled, saying that they’ve never seen or heard of any Jews. One man says that he knew a few Jews, but could not provide any details.

This is what happened to Gabrielle Zilkha, until an age old Jewish resource came to her: a Jewish mother.

Gabrielle’s mom searched the Internet and found a brief reference to a Jewish group in a small rural village quite far from Accra, the capital of Ghana, where Gabrielle was staying.

Although skeptical, Gabrielle called and arranged a visit. After a day-long bus ride to the remote village, she asked a cab driver about a man named Joseph, the contact name she was given. It drew a blank. She added, “he’s a Jew.” The driver’s face lit up: “Oh, OK.” He drove her to a house where she was welcomed and taken to a guest room. When the door opened, she was staring at a large Star of David on the wall.

This is where filmmaker Gabrielle Zilkha’s journey into Judaism in Ghana –and the inspiration for her documentary film, Doing Jewish: A Story From Ghana — began.

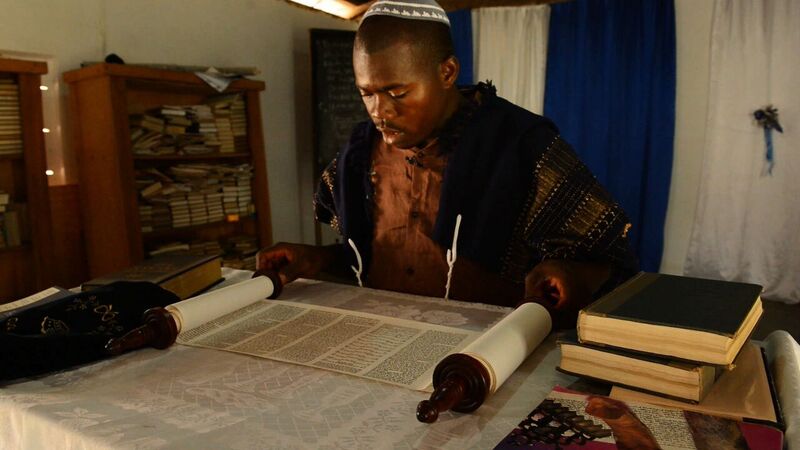

In that moment, though, looking at the Star of David she wondered: “Is this just a token or do they really practice Judaism?” That question was answered the next morning, the Sabbath, when Gabrielle entered a small crude building that was their synagogue.

To her astonishment she saw a Torah, men with yarmulkes (skull caps) and talits — and the entire congregation of black African men, women and children chanting prayers in Hebrew.

I interviewed Gabrielle to find out more about this intriguing community.

Bernard Starr: That synagogue experience must have been quite a shock.

Gabrielle Zilkha: It was indeed. I’m not a frequent synagogue-goer … but there was something quite beautiful about finding a sense of familiarity as a foreigner. This synagogue also felt so remote from other Jewish communities and institutions, and I found it quite moving to see a people so dedicated to their Jewish culture in what seemed like a vacuum.

Q: I’m sure you had lots of questions.

A: Tons. How did Judaism get here? How long had they been practicing? Where did they learn these particular Ashkenazi tunes? What is the story here?

Q: One of the remarkable discoveries that you made was that this sect of Jews was once part of a Christian community. Then, in 1977, they identified themselves as Jews. Why did they become Jews.?

A: Well, they didn’t actually become Jews. It’s a bit more nuanced than that. I think they would say they discovered their Judaism — a Judaism that was always there. I see the Sefwis, this Jewish community, as having two Jewish beginnings. First, they have their ancient Jewish ancestry — their own origin story, so to speak.

Sefwi oral history suggests two origins of Jewish ancestry: some believe they are descendants of a lost tribe of Israel expelled from the Kingdom of Israel in the 8th century BCE, [and] others point towards Sephardi Jewish ancestors who migrated southwestwards after the Iberian expulsion. In either case, the labels of Jewish, Judaism andJew were not used by the Sefwis for centuries. In fact, it wasn’t until a Sefwi man named Aaron Ahomtre Toakyirafa had a vision from G-d in 1977 that the customs that the Sefwis had been practicing for centuries — keeping kosher, keeping the Sabbath, menstruation practices (niddah), hand washing rituals and circumcision — were [understood to be] part of the ancient religion of the Hebrews.

Aaron is credited as the founder of the community because it was through his vision and leadership that the community discovered that what they had been practicing was called Judaism and they weren’t alone — that there were other people in the world called “Jews” who were part of the very same religion.

Q: On reflection, their connection to ancient Jews and Judaism is not implausible, since DNA testing has traced the black South African Lemba Jews to Moses’ brother Aaron — making them descendants of the priestly class of Jews.

A: I think it is plausible even without the existence of the DNA analysis. … Our western bias tends to value history validated by science and the written word over and above the information carried out by oral tradition. [Their oral tradition] is not simply a singular recollection of “how things came to pass” but a collective memory that is vetted and agreed to by many people over generations.

Q: But wouldn’t DNA analysis be welcome and of value and interest?

A: Indeed, it does make one curious about what story the Sefwis’ DNA would tell. Though it is important to clarify that genetic testing has its limitations in defining Jewishness or Jewish roots. The Jewish identity is much more than a genetic lineage — it is a complex mix of religious and cultural factors that are undetectable by DNA analysis.

Q: Once they decided they were Jews, how did these people know how to practice Judaism?

A: Great question. Before connecting with Jews from the outside world, Aaron and a group of the Sefwis known as the House of Israel studied the Old Testament and interpreted what they read into practice as best as they could. They combined what they learned from the Old Testament with their traditional Sefwi prayers — and from my observation, borrowed stylistic elements of Christian worship, even though they reject the tenets of Christianity.

Q: Did they get help or guidance from outside Jewish organizations?

A: Yes. Once the Sefwis got in contact with Jews from the outside world, they received educational materials and resources to advance their Judaism. The United Israel World Union was the first organization to have contact with the Sefwis. The community also hosted many volunteers who would teach Jewish practices to the community.

Most recently, Alex, one of their leaders, studied Judaism for four years at a yeshiva in Uganda under Rabbi Gershom Sizoumu. Later, they connected with other Jewish organizations that provided resources and educational materials. This was a real turning point, as shown the film. These outside contacts affirmed that they were no longer alone — that they belonged to something bigger than themselves.

Q: Didn’t Kulanu, the Jewish organization that supports remote Jewish communities, come to their aid?

A: Yes, Kulanu got involved with the Sefwis in the mid-90s. Kulanu facilitated a greater flow of communication, information, donations, people and resources between the Sefwis and the rest of the world.

Q: Your film focuses a lot on Alex — an extraordinary person who is fiercely dedicated to Judaism, who has a heartfelt dream of becoming a Rabbi. How do you explain his passion?

A: I’m glad you took note of Alex’s passion. Alex is motivated by what I would imagine are the same factors that motivate many religious leaders: a sense of one’s spiritual destiny, a loyalty to ancestors, a deep desire to lead a community to a better life spiritually and practicality, and a need to understand the meaning of life. Alex is also Ghanaian, and Ghana is a devoutly religious place. So the passionate pursuit of any religion is more the norm there than it is in Canada.

Q: Is this community growing.? Has it influenced others?

A: It is growing in numbers, but not necessarily in practice. As we mention in the film, the community is attracting a lot of bright young people, mostly men, who are increasingly questioning Christianity as “the right” faith, and are seeking other answers. Furthermore, my conversations with some of these new members revealed a certain cynicism towards Christianity and Islam — the dominant religions in Ghana — as products of colonialism. I thought that was just fascinating. As for practice, I think the community is at an unfortunate standstill. I think the Sefwis would agree with me in saying that the one thing they really desire is substantive and sustainable Jewish education.

Q: Is Judaism taking root elsewhere in Ghana

A: There is another Jewish community that has popped up in Accra, Ghana, which is rather large. And while I am unsure of whether the Sefwis influenced them, they are in contact with one another.

Q: What about antisemitism? Are they discriminated against?

A: The Sefwis faced persecution when they first declared themselves as the House of Israel, and rejected the tenets of Christianity and Islam. They were ostracized, [and] some were even thrown in jail and subject[ed] to violence. However, within the context of the wider Jewish story, their experience of antisemitism is fortunately very minimal. Today, the discrimination they face is very[small] — perhaps some ignorant name calling here and there. Otherwise, they are respected and live peacefully in and amongst their neighbors of other religions.

Q: In the United States, Jewish leaders worry about the future of Judaism — with defections, rampant secularism and high rates of intermarriage. Your film shows another side of that story: that Jewish revival can spring up in the most unexpected places. Do you see a trend here?

A: I’m so glad you picked up on that. I do see a surprising trend here — the rise of Judaism in Africa. There is what is called a “Judaizing” movement in Africa, where a growing number of Africans are identifying themselves as Jews or Hebrews or Israelites. Where this gets very complicated is in the definition of a Jew.

Will these newly declared Jews be recognized as Jews by traditional Jewish authorities? Some newer Jewish communities in Africa are even combining Judaism with other religions, making a Judaism of their own. Many would argue that this means they are not in fact Jewish or practicing Judaism but are actually “watering down” an ancient religion and tradition. It would be great if we could all get on a conference call and settle this, but if we haven’t resolved this controversy in the last few millennia, we are not likely to [do so] now. Regardless of where one places the boundaries, I think Judaism can serve as an entry point to learn about other people, and that to me is very beautiful.

Bernard Starr: Thanks, Gabrielle, for your gift of this film. It’s a fascinating , engaging and inspiring story of Jewish renewal. Where is it available for viewing?

Gabrielle Zilkha: Thank you. The next screening is at the Maine Jewish Film Festival in March. After that, please visit our website to keep up to date on screenings.

The Jewish Film Festival, sponsored by the Film Society of Lincoln Center in association with New York City’s Jewish Museum, screened the US premiere of Doing Jewish: A Story From Ghana on January 11, 2017. You can view the film’s trailer here.

Bernard Starr, PhD, is Professor Emeritus at the City University of New York (Brooklyn College). His latest book is Jesus, Jews, And Anti-Semitism In Art: How Renaissance Art Erased Jesus’ Jewish Identity & How Today’s Artists Are Restoring It.

Palestinian Prime Minister Announces New Reform Package

Palestinian Prime Minister Announces New Reform Package France: Man Suspected of Abducting, Raping Jewish Woman ‘to Avenge Palestine’

France: Man Suspected of Abducting, Raping Jewish Woman ‘to Avenge Palestine’ Israel Intensifies Strikes Across Gaza, Orders New Evacuations in North

Israel Intensifies Strikes Across Gaza, Orders New Evacuations in North Iran Threatens to Annihilate Israel Should It Launch a Major Attack

Iran Threatens to Annihilate Israel Should It Launch a Major Attack ‘Completely Baseless’: Reports of Mass Graves at Gaza Hospitals are False, IDF Says

‘Completely Baseless’: Reports of Mass Graves at Gaza Hospitals are False, IDF Says Columbia University Shutters Campus as Jews Fear for Safety, Critics Call for President to Resign

Columbia University Shutters Campus as Jews Fear for Safety, Critics Call for President to Resign ‘Hamas, We Love You!’ A List of the Chants, Statements From Columbia University’s ‘Gaza Solidarity Encampment’

‘Hamas, We Love You!’ A List of the Chants, Statements From Columbia University’s ‘Gaza Solidarity Encampment’ ‘Useless Pigs’: Anti-Israel Demonstrations Rage at Yale University, Forcing Police Intervention

‘Useless Pigs’: Anti-Israel Demonstrations Rage at Yale University, Forcing Police Intervention Anti-Israel Protesters Interrupt Chelsea Handler Comedy Show Because of Her Support for Jewish State

Anti-Israel Protesters Interrupt Chelsea Handler Comedy Show Because of Her Support for Jewish State Israeli Hostage Families Make Passover Plea for Return of Missing Loved Ones

Israeli Hostage Families Make Passover Plea for Return of Missing Loved Ones

‘Completely Baseless’: Reports of Mass Graves at Gaza Hospitals are False, IDF Says

‘Completely Baseless’: Reports of Mass Graves at Gaza Hospitals are False, IDF Says Iran Threatens to Annihilate Israel Should It Launch a Major Attack

Iran Threatens to Annihilate Israel Should It Launch a Major Attack Israel Intensifies Strikes Across Gaza, Orders New Evacuations in North

Israel Intensifies Strikes Across Gaza, Orders New Evacuations in North France: Man Suspected of Abducting, Raping Jewish Woman ‘to Avenge Palestine’

France: Man Suspected of Abducting, Raping Jewish Woman ‘to Avenge Palestine’ Palestinian Prime Minister Announces New Reform Package

Palestinian Prime Minister Announces New Reform Package